Review: In 'Little Bear Ridge Road' on Broadway, Laurie Metcalf shows us a woman so alone on that couch

Published in Entertainment News

NEW YORK — A subset of people, when faced with, say, cancer, prefer to keep their health crisis a secret. It often comes from a detestation of being treated as a victim, or a desire to protect loved ones from pain. But it can also be about autonomy.

In Samuel D. Hunter’s beautiful play “Little Bear Ridge Road,” the remarkable actress Laurie Metcalf plays such a woman: Sarah, from red-state America, the playwright’s native Idaho. Sarah is a gruff, determined American who hates dependency with every fiber of her being. “It’s no one’s business but mine! It’s my body!” she shouts at one point. “Can I just have control over one thing, just my own damn body?”

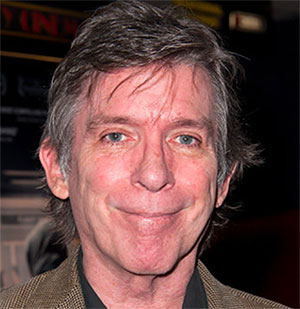

“Little Bear Ridge Road” originated with a commission and this same cast at the Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago, and is one of three productions within a year to move from our storied, 50-year-old company to Broadway. That’s courtesy in this case of the once-exiled, now-returning producer Scott Rudin, a longtime collaborator with Steppenwolf, as well as of Metcalf and the gifted director, Joe Mantello, who, having directed “Wicked,” now clearly wants to spend his remaining time as far away from big-budget spectacle as possible.

“Little Bear” has just four characters: Metcalf’s Sarah, her nephew Ethan (Micah Stock), Ethan’s potential boyfriend James (John Drea), and, briefly, a health care worker (Meighan Gerachis). The only physical item on Scott Pask’s deceptive set is a beige couch.

The story could not seem simpler. Ethan, a struggling millennial with an MFA in creative writing, of all practical things, has returned home from Seattle to deal with his meth-addict father’s estate, such as it is. Ethan, as they say in the musical “Once,” is stuck. And to a large extent, “Little Bear” is about stuckness, by which I mean the inability to pack away the past sufficiently to make necessary changes in your life.

But the central question of these 90 minutes of theater is not just whether or not aunt and nephew, who really are all each other has, can overcome past guilt and resentment to forge a functional relationship. It’s whether they can find it in their hearts and minds to admit they need one. You know, assuming they actually do. (I actually sat there wondering how much I need other people and thinking maybe not as much as I think, but I digress.)

If you are someone who finds it hard to talk about personal feelings, or love someone in that category, especially if that someone is in existential crisis, you will likely find this play very moving.

Even by Metcalf’s lofty standards, this is one stunner of a performance.

I’ve seen it twice now, and it has only deepened. At one point, a moment I don’t want to spoil with more detail, Sarah’s pain gets vocally manifest in a great, guttural howl, or it would if Sarah could sufficiently unblock her voice.

Metcalf actually is one of the few great American actors who can show you both of these things at once: the feelings her character can express and those she cannot. If you are a student of how actors illuminate subtext while simultaneously honoring how trapped some Americans get in repressed feelings, it’s a revelation. Truly. And Stock, who puts everything this young actor has into the ring with this heavyweight prize-fighter, rises to meet Metcalf at every moment he can.

The other thing about Metcalf is that she is determinedly unpretentious. Most characters in plays are far more articulate and self-confident than we are in reality (look at all the chatty people on Broadway right now), and thus most actors learn to be the same.

Hunter even includes one of those very characters in this play; the possible boyfriend who has had a charmed life by comparison and thus struggles to understand a different kind of childhood. He’s sweet, verbose and clueless and Drea has the assignment down.

Metcalf has the opposite assignment. Her secret weapon is her disdain for over-articulation, her empathic determination to honor those who struggle to speak for themselves, and that’s exactly what Hunter brings to the party as a playwright.

It’s a spectacular combination that is, in today’s American theater, unique.

———

At the Booth Theatre, 222 W. 45th St., New York; littlebearridgeroad.com.

———

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments