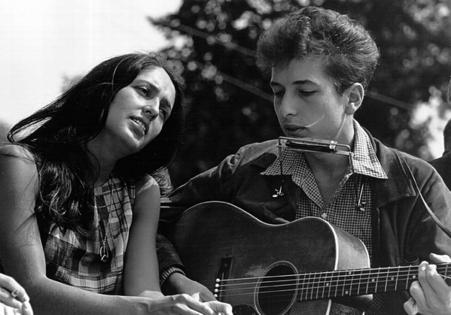

New bootleg boxed set highlights Bob Dylan's earliest and rarest made-in-Minnesota recordings

Published in Entertainment News

MINNEAPOLIS — How did Bob Zimmerman of Hibbing become Bob Dylan of Everywhere?

Last winter’s Timothée Chalamet movie “A Complete Unknown” tried to demonstrate the evolution by looking at Dylan’s early New York City years. Now we can experience the transformation musically in the bard’s own voice in “Bob Dylan’s Bootleg Series Vol. 18: Through the Open Window, 1956-1963,” which will be released Friday.

This boxed set contains the first known recording Bobby Zimmerman made at age 15 in St. Paul as well as songs he performed in Minneapolis houses and apartments, even songs he sang in concert at Coffman Memorial Union at the University of Minnesota.

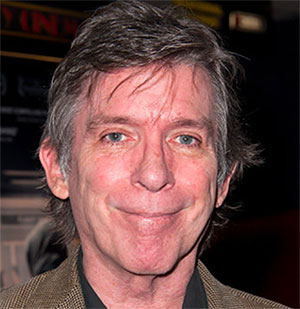

“We wanted this to be a narrative, to tell a story of Dylan’s maturation from Christmas Eve 1956 right through the Carnegie Hall concert in 1963,” said Sean Wilentz, coproducer of the boxed set. “It’s a complicated, multilayered story. It shows you Dylan as the disciplined hard worker. Genius doesn’t just come to you. You hear Bob Dylan become Bob Dylan.”

Like the mysterious Dylan himself, Wilentz doesn’t know how Columbia Legacy, an archival record label, found all the tapes that make up the 139-track set, including 48 never-released performances.

“Dylan’s office had been collecting this over the years. The very first recordings were only found recently,” Wilentz said via Zoom this month. “Basically, we were presented with hundreds of hours of tape. The quality wasn’t always so great. They gave us the tapes and we did the carving.”

Wilentz said there is a small network of Dylan collectors, some of whom are close to Dylan’s office.

“It’s a strange business,” said Wilentz, a Princeton University history professor. “These tapes have been lying around, and people don’t know that they’re there. Sometimes it’s not the person who did the taping, it’ll be a son or daughter who ends up with them and they don’t know what to do with them. So, they end up with us.”

Unlike previous volumes in the Dylan Bootleg Series, this one is not heavy on outtakes from recording sessions. This boxed set contains lots of recordings from living rooms as well as proper concerts.

Wilentz, author of 2010’s acclaimed book “Bob Dylan in America,” did not speak with Dylan for the 125-page liner notes for “Through the Window.”

“I try not to get too close to Bob because I want to do my own thing,” he said. “I don’t know how much he’s invested in any of this stuff. He’s made the records. He thinks: Why do we have to hear it again?”

Wilentz did consult with Jeff Rosen, president of Bob Dylan Music Co. and the reclusive icon’s close adviser, and co-producer Steve Berkowitz of Columbia Legacy, who has worked on the entire Dylan Bootleg Series.

After hours of listening over decades, Wilentz, who grew up in Greenwich Village, feels Dylan learned a lot in the Village “but a lot of the best performances are actually in Minneapolis — at least through ’63.”

He kept returning to Minneapolis to hang with old friends such as Tony Glover (aka Dave Glover), John Koerner and Dave Whitaker.

“Tony used to talk about how he left kind of ordinary, no big deal, and he’d come back and he’s unbelievable,” Wilentz said. “They couldn’t believe it happened so quickly.

“These friends are soulmates of his, Tony in particular. This means a lot to him. He’s very, very relaxed. He’s not playing the big guy who made it out to New York and met Woody Guthrie. They’re peers. They’re hanging out with each other.”

Let’s go to the tapes, at least the ones with Minnesota connections.

Dec. 24, 1956

Terlinde Music Shop, St. Paul

“Let the Good Times Roll”

Dylan took the Greyhound Bus from Hibbing to St. Paul, where his cousin Howard Rutman and their summer camp friend Larry Kegan lived. They went to Terlinde Music Shop on West 7th Street where customers could make an acetate recording quickly for a modest price. The teenagers cut a handful of mostly doo-wop songs, lasting 30 to 60 seconds each.

“They show their enthusiasm far outstripped their talent. Or at least their abilities,” Wilentz said. “We start off with the first cut with ‘Let the Good Times Roll,’ the Shirley and Lee version. What I hear on the tape, Bob Zimmerman is banging away on the piano. He’s kind of the leader of the group as far as I can tell. He knows all the words. He calls out the chords out of the piano.

“When Dylan was a kid in Hibbing, he was the kid who took more risks than other people did. He was unafraid about playing rock ‘n’ roll on the Hibbing High School stage even if the curtain was going to be thrown down on him. He had a side of him that was bookish and studious, and the other side was out there. You can hear some of that even at age 15 in these recordings made in St. Paul.”

September 1960

Bob Dylan’s apartment, Minneapolis

“San Francisco Bay Blues” and “Jesus Christ”

Cleve Petterson was a Twin Cities teenager with a tape recorder who asked Dylan — “who was nothing special, even on the Dinkytown scene” Wilentz said — if he’d play for him. They went to Dylan’s apartment above Gray’s Drug in Dinkytown. Among the songs was Woody Guthrie’s “Jesus Christ.”

“His playing is rudimentary, he’s got a long way to go still,” Wilentz observed. “He’s not simply trying to imitate Guthrie. He has that Okie twang, but you can already hear him trying to make these songs his own rather than simply being a copycat.”

May 13, 1961

Coffman Memorial Union, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis

“I Ain’t Got No Home in This World Anymore”

Dylan returns to Minneapolis in May 1961 to perform at a folk festival at the University of Minnesota, which he dropped out of a year earlier. He’s only been in New York for a few months.

“We have a new recording of the Guthrie song. People have never heard that one before,” Wilentz said. “I’m not supposed to know what the provenance is. This is a very subterranean world of collectors. I’d just as soon not know.”

Aug. 11, 1962

Dave Whitaker’s home, Minneapolis

Introduction and “Tomorrow Is a Long Time”

In the summer of ‘62, Dylan is talking to his friend Glover’s tape recorder. The singer’s girlfriend, Suze Rotolo, is on a prolonged trip to Italy and he’s “feeling more than kind of blue,” Wilentz said. “And he talks about it to the tape. ‘I’ve written a song. Well, only the last verse. And now we’re going to sing it.’ He says, ‘It’s not in my style. This is Pete Seeger style. Do you know who Pete Seeger is? He’s Mike Seeger’s older brother.’ Then he starts singing the song and it’s an early version of ‘Tomorrow Is a Long Time.’ That’s an amazing moment. You could hear how his artistry began to take shape.”

July 17, 1963

Tony Glover’s home, Minneapolis

“Eternal Circle,” “Liverpool Gal,” “West Memphis”

“This one was kept under lock and key,” Wilentz said. “It’s amazing for all kinds of reasons. The one that’s going to get the most attention is ‘Liverpool Gal,’ which is a song Dylan wrote about his time in London. That winter of ‘62-‘63. No one’s heard it. It’s been talked about. It’s not a No. 1 Dylan but it’s a very good song.”

Dylan also sings a new song called “Eternal Circle.”

“He points out what that song is all about. The banter is very interesting, though not as interesting as the song. At one point, he and Glover start jamming. They do a song called ‘West Memphis.’ They were making it up as they go along. To hear Bob Dylan and Tony Glover do a duet, that was precious. It’s a couple of guys sitting around having fun. It’s not a performance for the ages. But it’s two very talented old friends playing this new music in new ways.”

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC

Comments