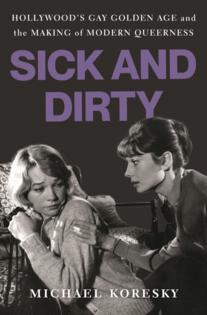

Column: The new book 'Sick and Dirty' examines the not-so-hidden queerness of classic Hollywood

Published in Books News

You’re a kid. You catch a few seconds of something strange on TV. Those few seconds have a way, sometimes, of paying a call decades later.

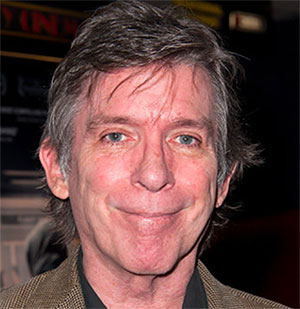

It happened to author, critic and film curator Michael Koresky. His absorbing new book is “Sick and Dirty: Hollywood’s Gay Golden Age and the Making of Modern Queerness,” and just as he was writing its final chapter, he dredged up a fuzzy memory of seeing something on his grandmother Bertha’s TV set when he was around 10.

“We were over at my grandmother’s place in Newton, Massachusetts, where we always went on Jewish holidays,” he says. “She always had the TV on. This time it was set to PBS, which played movies in the afternoons, I remember. I walked by the TV and saw this little snot-nosed girl, sitting in the back of a car, looking very angry, whispering something in this older woman’s ear, and the woman’s face just falls, horrified. It looked like a horror movie.”

And then: “My grandmother’s walking in and out of the room, carrying loaves of challah, and she stops and looks at the TV, and she sees me looking, and she says to me: ‘That one,’ pointing at the girl. ‘That one’s a troublemaker.’ And she didn’t tell me why.” Years later, Koresky found out why.

The film was the 1961 version of “The Children’s Hour,” Lillian Hellman’s pathbreaking 1934 drama about “a lie perpetrated by this malicious little girl, about her schoolteachers being lesbians, carrying on an affair,” Koresky says. His book takes its title from a self-lacerating line spoken by the tragic closeted lesbian played by Shirley MacLaine.

What Koresky achieves here is a sharp, sometimes personal investigation of some choice Hollywood projects, beginning with the massively altered 1936 “Children’s Hour” adaptation, “These Three.” Many of the films under review were derived from sensational source material optioned by a studio only to be de-sexualized (at least on the page) and rendered the most distant of cousins to their sources.

Rules were rules then. The Production Code Administration enforcement went into full practice in 1934, bringing the raucous pre-Code enforcement era to a halt. “Sick and Dirty” isn’t a pre-Code book. It’s a Code book, about what happened next, what then-transgressive sexual images — furtive, oblique, often partially or fully erased — sneaked into the slyly suggestive “Rope,” for example, directed by Alfred Hitchcock. Its homicidal lovers plainly are as gay as a day in May, yet just closeted enough to pass muster with the Code.

Koresky, senior curator of film at New York City’s Museum of the Moving Image, delves into the screen versions of “Tea and Sympathy,” as well as what he calls “the unparalleled derangement” of Tennessee Williams’ “Suddenly, Last Summer,” with its climax of the Elizabeth Taylor character’s sexually voracious, manipulative cousin literally eaten alive by young boys he has “procured” for himself.

“We know these movies come from an era of censorship,” says Koresky. “We know the Production Code only allowed films to say and show certain things. Yet this time of great restriction, the mid-’30s to the early ’60s, was also arguably the greatest period ever for American cinema.” Our conversation is edited for clarity and length.

Q: How did you land on the handful of films you focus on in “Sick and Dirty”?

A: I wanted films from the key decades to reflect some idea of forward motion, in each era. It’s a history of Hollywood, roughly 25 years of it, and it’s not really an alternative history. It’s the history of the Code, and how these films are connected, as well as connected to the culture at large.

I write about “Rebecca” (Hitchcock’s 1940 Oscar winner, with the plainly lovelorn Mrs. Danvers as relished by Judith Anderson), which could’ve had its own entire chapter. “Red River” (the Howard Hawks/John Wayne/Montgomery Clift Western from 1948) could’ve had its own chapter. And there were smaller films like “Desert Fury” (1947, Western noir), which is one of the great gay Hollywood films of all time.

Q: Can you talk a bit about how Hollywood’s reliance on Broadway influenced the occasional, forbidden images of gay and lesbian life, usually tragic, of course, and always cleaned up for the Code’s purposes?

A: Sure. The entire book is anchored by “The Children’s Hour,” and (playwright) Lillian Hellman is the stealth protagonist, in a way. “These Three” was the first adaptation made in Hollywood from that play, a prime example of how you’d get these hit plays on Broadway, and Hollywood would be so envious of the scandal and sensation and success of them, and they’d buy the film rights immediately — knowing they’d be ordered by the Production Code essentially not to make movies out of them unless they changed every single thing. They’d have to rework entire plotlines. With “Tea and Sympathy” (director Vincente Minnelli’s 1956 version of the Robert Anderson play about an “unmanly” teenage boy’s torturous coming of age), MGM paid $400,000 for it, knowing they wouldn’t be able to make it the way they wanted to.

Tennessee Williams’ plays, and Hollywood’s versions, made him one of the most important figures in cinema history, I think, in terms of how the Production Code was tested, challenged, how things progressed, and led to the amendment of the Code language. People were craving this prestige shock material. And then, in 1959, to have something like “Suddenly, Last Summer,” which is about as out-there as a movie could get in 1959, to have that somehow get through largely intact …

Q: I still can’t quite believe it happened.

A: Once that film got released, and became a hit, and an Oscar-nominated hit, all bets were off.

Q: Until reading “Sick and Dirty,” I didn’t know about how a Loyola University meeting here in Chicago led to the creation of the Production Code in 1934.

A: The Chicago Catholics were central to what Hollywood became. When the Catholic Church during the Depression threatened to boycott Hollywood, that meant 20 million potential lost customers. Depression-era Hollywood was terrified of losing everything. It couldn’t ignore them. And under Joseph Breen, with the strong influence of the Roman Catholic National Legion of Decency, the Code was truly enforced.

Q: Where are we now as a film culture?

A: It’s a hard question. I have such conflicting feelings about the culture in general. This year, I mean look at how corporate sponsorship of Pride Month has dried up because of political pressure, and the pullback on DEI. Political reality dictates a lot. And it’s affecting everything right now.

But things haven’t changed all that much in Hollywood. You look at a movie like “Love, Simon” (2018), the first Hollywood film with a gay teen protagonist. Coming out story, very bland. I had conflicted feelings about; I’m not sure who it’s geared toward. On the other hand, if I’d seen that movie as a teenager growing up, it would’ve been a seismic event in my life.

Q: Your book pushed me to see a movie I’d somehow never made time for: The first William Wyler version of “The Children’s Hour” from 1936. Such a wholesale whitewashing! But so good! And with Wyler’s direction of Merle Oberon and especially Miriam Hopkins, it’s sublimely clear these two college friends meant so very much to each other.

A: It’s the great example of a completely censored film that’s also a really interesting one, and beautifully made. When I teach film, I preface a screening of something like “Tea and Sympathy” by saying: ‘These movies have some very progressive elements. They also have some very conservative elements. Now, let’s talk about how those elements interact.’ With “Tea and Sympathy,” the students responded to it, not as a relic of a former time. Many wrote about how it related to their own lives, and how it feels to be young and not know who you are.

I’m never going to admit actual nostalgia for a time of movie censorship. But you have to admit that this time of restriction holds sway over our imaginations, to this day.

____

Michael Phillips is a Tribune critic.

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments