Trial starts in LA lawsuit alleging Instagram and YouTube knew apps harmed kids

Published in Business News

A landmark civil trial that will ask jurors to decide whether social media companies can be held liable for pushing a product that they allegedly knew was harmful to children began Monday in Los Angeles County Superior Court, with attorneys sparring for more than four hours in combative opening arguments.

The closely watched test case could rewrite the rules of engagement for social companies and their youngest users — and leave tech titans on the hook for billions in damages.

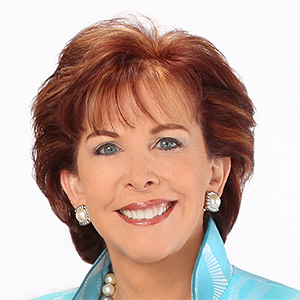

Judge Carolyn B. Kuhl admonished the 18 Angelenos — 12 jurors and six alternates — not even to talk to their own therapists about the bellwether trial, the first among thousands of similar suits currently pending together in state and federal courts. Two other defendants, TikTok and Snap, settled for undisclosed sums to avoid the current trial.

The plaintiff, a Chico, California, woman referred to as Kaley G.M., said she became addicted to social media as a grade schooler, and charges that YouTube and Instagram were built to snare very young children and keep them hooked, despite known design flaws that made their products dangerous. She appeared briefly in court Monday.

"They wanted to capture Kaley before she even hit puberty," said Mark Lemeir, one of the young woman's attorneys. "It's addiction by design."

He vowed to hammer Mark Zuckerberg — head of Instagram parent company Meta — on that point when the chief executive is called to testify in coming weeks.

Despite public vows to keep kids under 13 from using its product, internal Instagram documents shown in court Monday morning depicted aggressive efforts to woo children much younger.

Internal documents from Google appeared to show incentives to shift children not yet out of diapers from the gated YouTube Kids app to the all-ages platform.

The tech companies have hit back on those claims, saying G.M.'s attorneys had twisted internal documents to paint their platforms into cartoon villains, attempting to hold corporations responsible for other kids' misbehavior and G.M.'s own childhood traumas.

"Plaintiffs' lawyers have selectively cited Meta's internal documents to construct a misleading narrative, suggesting our platforms have harmed teens and that Meta has prioritized growth over their well-being," Meta said in a statement last month. "These claims don't reflect reality. The evidence will show a company deeply and responsibly confronting tough questions, conducting research, listening to parents, academics, and safety experts, and taking action."

Families have been trying to hold social media companies accountable for harms to young users for more than a decade, so far without success. The platforms are protected by a powerful 1996 law called Section 230 that shields internet publishers from liability for user content. They are further insulated by the 1st Amendment's safeguards on freedom of speech.

Plaintiffs in the Los Angeles bellwether and related cases have sought to get around those protections by relying on claims about corporate negligence and flawed product design, similar to those brought against opioid maker Purdue Pharma in recent years and Big Tobacco in the 1990s.

Observers said a win in court could function much like a Silicon Valley initial public offering, setting a cash price for addiction liability and helping establish a dollar value for lives lost to suicide, anorexia, stunt challenges and sextortion — all harms allegedly inflicted or amplified by social media.

"It's really a valuation event," said Jenny Kim, an attorney in a related lawsuit. "If this plaintiff is able to secure a big verdict, it'll set an anchor value for the rest of the cases that go to trial."

Still, experts on both sides agree the legal bar for G.M. and other plaintiffs is high. In order to rule in her favor, jurors will have to parse the harmful actions of fellow users — including her high school bullies and adult men sending her unsolicited nudes — from design decisions made by the companies themselves.

During his two-hour-long opening statement, Lemeir showed a raft of internal documents, including a Google memo from the early 2010s saying, "[the] goal is not viewership, it's viewer addiction," and one from Meta in 2018 saying, "if we want to win big with teens, we must bring them in as tweens."

Lawyers for the companies sought to portray those items as cherry-picked distortions, saying any harms G.M. suffered as a result of her social media use flowed from other users, not the products themselves.

YouTube's attorney went further, telling jurors the platform wasn't social media at all and shouldn't be lumped in with entities such as Instagram. Even if attorneys can prove social media addiction exists, the company's lawyers argued, that determination is not applicable to the video-sharing platform.

The company allegedly tried to convince parents to trust their young kids alone with the app.

"Parents need a babysitter to entertain their kids," Youtube said in an internal 2012 document, shown by the plaintiffs on Monday in court. "They want to trust that they can leave their child alone with the app to be safely entertained."

The trial comes at a moment of deepening public anxiety over social media's impact on children, and growing distrust of the corporations that operate the platforms.

California banned phones in public school classrooms beginning in January, largely in response to the infiltration of social media. Many private schools have gone further, pressuring parents to forbid the apps at all until a certain age and to tightly control use thereafter.

Lawyers for YouTube emphasized that defendants' fates are "not tied together" and that jurors could find one company liable but not the other.

That strategy may prove successful: Research suggests many users — especially parents — do see the products differently.

But banking on the same outcome in court could backfire, Kim said.

"Juries have a tendency to lump all the defendants together in these type of cases," Kim said.

Even if G.M. loses in court, testimony and documents from weeks-long trial could further tarnish corporate giants already on the back foot with many parents and younger users — a top goal for many of the observers who massed on the courthouse in downtown L.A. at daybreak Monday for the chance at a seat in the gallery. Several wept openly as documents were shown.

"All of our kids are on our shoulders," said Lori Schott, whose daughter Annalee died by suicide after a years-long struggle with what she described as social media addiction. The companies "knew that their design tactics were harming young girls' mental health, and they didn't back off. I would have parented a lot differently if I could have seen what we know now in this case."

©2026 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments