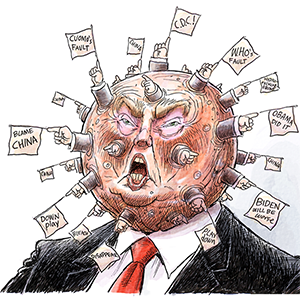

Minnesota soybean farmers fear lasting scars from Trump's trade war with China

Published in Business News

TRACY, Minnesota — Months into a trade war with China, steel grain bins across rural Minnesota sit plump with soybeans without a market, and farmers are nervously eyeing balance sheets.

On Wednesday, news broke across an ocean that, ahead of a planned meeting between President Donald Trump and China’s president, Xi Jinping, China had purchased three cargoes of U.S. soybeans, ending a monthslong embargo. The news was welcome. But more would be needed.

In southwestern Minnesota, including Tracy, local economies follow the soybean markets. In good years, farmers use profits to buy pickups from area car dealerships and make down payments on land. In lean years, they tighten belts.

Trump’s trade war with China could not have come at a worse time. It’s the lean years in the soybean markets, and up until this year every third row went to China.

So, farmers argue, they are losing money on every acre of soybeans they plant because of a crisis not directly of their own making.

And the crisis affects the entire state. Soybeans are Minnesota’s largest export — generating $2.4 billion annually. Now farmers fear they are seeing the start of a permanent market shift that will change the soybean industry.

Farm country and state officials are all watching closely this week. Trump meets Thursday with Xi Jingping, and a blueprint for a possible deal floated Sunday evening sent soybean markets 20 cents higher overnight.

After another year of economic distress, being stuck in the middle is a pain felt particularly hard in areas politically friendly to the president.

“I’ll be honest, I kind of trusted him that he would be able to work out these trade deals way sooner,” said Jay Fultz, a Cottonwood County farmer who finished his harvest earlier this month.

Shadow of past farm crisis

Looming behind the current crisis is what happened to wheat farmers a generation ago when President Jimmy Carter’s embargo of the Soviet Union in 1980 permanently curtailed wheat acres in the Upper Midwest.

There never was that one big customer again.

That’s what soybean farmers are worried about now — that while new markets will be found, they won’t add up to the heft of China.

In 2023, Minnesota exported nearly 4 million metric tons of soybean meal, which is largely used to feed hogs. Many grain analysts are wondering, where does that go without China?

“There’s a secular risk that this is not going to cycle back up,” said Megan Roberts, an agricultural economist with Compeer Financial in Mankato. “There are absolutely discussions right now we’ve fundamentally had a change to the supply-and-demand of this commodity.”

China seemed the answer for this century

It wasn’t many years ago that opening up trade with China was seen as the antidote to soybean farmers with fresh memories of the devastating 1980s, when crop farmers went bankrupt at rates unseen since the Great Depression.

When Gov. Arnie Carlson went to China on a trade mission in 1998, he brought along a soybean farmer, Don Nickels.

His son Audi Nickel now farms and teaches agriculture at the high school in Mountain Lake.

“(Dad) was frustrated just like anybody else and realized, ‘Hey, this is a way for me to make an impact on every soybean farmer — not just in southwestern Minnesota, but all over the country,’” Nickel said.

Nickel said his father, who died in 2022, watched with dismay during Trump’s first term when a trade war with China cost American soybean farmers an estimated $20 billion in profits.

Now, he wonders if his taciturn father, who was slow to criticize politicians, would be more vocal in his anger.

Audi Nickel, himself, picked up a teaching job to generate extra income to buttress against a farm failure.

“If I hit (like the) ’80s financially, I’d need to fall back on something,” he said.

As of late October, hope glimmers on the horizon for a resolution to the Chinese soybean embargo.

Currently, soybeans are trading at over $10 a bushel — a decent price that suggests the prospect of a trade deal is baked into traders’ expectations, Roberts said.

Stagnate markets taking toll

But the stagnate markets have already caused distress. This is the second year in a row farmers are expected to plant soybeans at a loss when factoring in their costs, which include fertilizer and seed.

Farmer defaults are spiking to levels not seen since before the pandemic. Earlier this month, Minnesota economic officials reported exports dropped 19%, a loss of $1 billion

Benya Kraus, president of the Southern Minnesota Initiative Foundation, said she’s witnessed on her own family farm outside Waseca a need to cut back on expenses. Car dealerships, fertilizer sellers, even food shelves needing donations all are feeling reverberations.

“When our farmers are hurting and need to tighten their financial wallet, the whole rural community feels it,” Kraus said.

New customers mean infrastructure costs

There’s some hope for domestic use of soybeans: biofuels.

“There’s no place else to go in the world to replace China,” said John Griffith, executive vice president of ag business at CHS.

Blending all diesel used on American highways with 2% soybean-based biodiesel could fill the China gap, Griffith added.

The soy industry sees national biodiesel policies as the most effective lever to pull to increase demand for soybeans. But that would require political support in Washington — and years, if not decades, to fully develop.

Even with export customers beyond China, re-engineering shipping lanes away from the Pacific to the Gulf of Mexico or the Twin Ports in Duluth is expensive. And South America’s increased production in recent years has led to a global glut of soybeans — in short, domestic markets are needed.

For a generation of farmers, the specter of China meant a growing, almost limitless market for soybeans.

Ed Usset, a grain marketing economist at the University of Minnesota, puts a graph up on the first day of class of China’s soybeans imports. In Minnesota fashion, he says it resembles a “hockey-stick.”

“Soybeans are a mirror of growth in the Chinese economy,” Usset said. “As the (Chinese middle class) had more money, they changed their diets.”

In other words, they wanted pork. And to feed those hogs, they needed feed. American soybean producers stepped up to fill those orders.

In Minnesota, where 70% of soy exports leave through the Pacific Northwest, entire rail terminals shifted. Trains got longer. Runs could happen as many as 2½ times a month from western Minnesota to the West Coast.

“There was tremendous growth,” Usset said.

In the early 2000s, soybeans even eclipsed corn briefly for number of acres planted across Minnesota. By 2024, 7.4 million acres were planted.

But, just like the first trade war, the Chinese embargo has raised existential questions about soybeans: Minnesota grows more than the U.S. uses domestically. Should it?

“We can’t utilize all the soybeans produced in this country,” said Pauline Van Nurden, an economist with the University of Minnesota Extension. She added that building out a partner to take China’s place would take years.

Politics shades farmers’ view of solutions

Back in Tracy, Fultz’s father, Dennis, is a lifelong Republican who voted for Kamala Harris last November. He says Trump undid decades of goodwill with China.

“The foreign buyers for corn, soybeans, pork, beef, they will go to the other places in the world,” Dennis Fultz said.

But Dennis’ son, Jay, who voted for Trump, retains faith in the president’s reputation as a dealmaker.

“We still have three more years for him to kind of figure things out,” Jay Fultz said. “I think there’ll be brighter times ahead.”

Even farmers who don’t share Jay Fultz’s optimism about the Trump administration agree on one point: They will plant soybeans again in the spring. It’s what they’ve always done.

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments